They sought out the supernatural, the unconscious and the strange and shared a mistrust of the acceptance of pure reason: Even though they were separated by approximately a century, we can see a surprising spiritual similarity between the Surrealist movement and German Romanticism.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), Romantic painter, also played a significant role in this phenomenon.

1 Surrealism and German Romanticism

With the publication of André Breton’s (1896–1966) Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, a movement was founded in Paris that had already existed informally for a number of years. In this foundational text, Breton—who, in his late 20s, was the leader of the movement—called for spiritual and societal renewal through art. The Surrealists took their name from the word “surrealisme,” coined by Guillaume Apollinaire in 1918. The word “surreal” literally means “beyond real”—a hint at the goals of the movement.

Still feeling the effects of the First World War, the Surrealists wanted to transcend the bounds of reason and gain access to the unconscious—by revaluating dreams and irrationality and through methods of automatism (“automatic” writing, drawing and painting without deliberation, with the aim of bringing the unconscious to the surface)

André Breton, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, René Magritte, Joan Miró, Lee Miller, Salvador Dalí, Meret Oppenheim and Dorothea Tanning are some of the central figures of this movement, which was strongly influenced by Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis.

Surrealism found expression in the fields of photography, painting, sculpture and film. Its ideas radiated far beyond the borders of France and Europe—and beyond the boundaries of its historical era.

With the movement’s increasing internationalization from the 1930s onward, Surrealist ideas also spread across Africa, Asia, and Central and South America. They found especially fruitful resonance in Mexico, for example, in the works of Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Olga Costa.

The world must be romanticized. That’s how you find the original purpose again.

Just make an effort to practise poetry.

The traditions within which the Surrealists saw themselves were as varied as the new group itself. The Surrealists were especially influenced by the writings of the Jena and Heidelberg Romantics.

The parallels, similarities and affinities between the two movements are illustrated in a 2025 exhibition at the Hamburger Kunsthalle.

Max Ernst, All Friends together | Au rendez-vous des amis, 1922, Oil on Canvas, 130 × 195 cm, Museum Ludwig, © Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln, © Image: 2025 VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Alongside the poetry and philosophy of the Romantic era, the visual arts of that period also left their marks in the works of Surrealism. Caspar David Friedrich, who gained significant popularity following the Centenary Exhibition of German Art (Jahrhundertausstellung Deutscher Kunst) in Berlin in 1906, was still largely unknown in France.

The Surrealist Max Ernst (1891–1976) played an important role in the spread of German Romanticism in France. The artist, a native of Brühl near Cologne, first discovered Romanticism as a student in Bonn. Throughout his lifetime, he was fascinated not only by the works of Romantic authors such as Novalis, Hölderlin, Schlegel and von Kleist, but also by the art of the Romantic period.

He would have seen some of Caspar David Friedrich’s original works in 1920 at the latest, when he visited the National Gallery in Berlin.

Alber Béguin’s 1937 study L’Âme romantique et le rêve (The Romantic Soul and the Dream) contributed significantly to Friedrich’s recognition value in France. Here, Béguin quoted Friedrich’s statement about an artist’s “inner vision” of an image. In addition, in 1939, the German art historian Madeleine Landsberg reproduced a few of Friedrich’s works in a contribution to the Surrealist periodical Minotaure (for example, Das Eismeer, Kreidefelsen auf Rügen, Mönch am Meer). Driven into exile in France due to her Jewish heritage, Landsberg published the text Caspar David Friedrich, peintre de l’angoisse romantique (Caspar David Friedrich, Painter of Romantic Anxiety) there. She depicted Friedrich as a deeply Romantic figure who was plagued by a “primal fear.” She examined Friedrich’s work from a psychoanalytical point of view, interpreting his moon landscapes, for example, as the expression of unfulfilled longing.

It is difficult to measure the influence Landberg’s article had on the Surrealist movement; however, the timing of her article is noteworthy: By 1939, Friedrich had long since been revered as the embodiment of a “German spirit” and appropriated by the National Socialists as their nationalist precursor, superelevating his “German” landscapes. In France, on the other hand, the Surrealists subversively made Friedrich their own, reinterpreting his images as antimilitaristic. More than a few members of the movement were active in the resistance.

Caspar David Friedrich, German Romanticism and Surrealism have a lot in common.

2

Inner Vision:

Making the invisible visible

Georg Friedrich Kersting, Caspar David Friedrich in his Studio, 1811

Caspar David Friedrich called for artists not to simply paint what they see, but to paint what the see inside themselves. This concept of “inner vision” placed the external natural world in the service of spiritual experience. Friedrich’s landscapes are not realistic depictions; rather, they arose from his imagination, composed artistically before his inner eye. But invention alone was not enough. Friedrich stated: “A landscape should not be invented; it should be felt.”

One hundred years later, the Surrealists also set out in search of an inner vision—albeit a much more radical and experimental one. Through approaches such as automatic writing (writing as freely as possible using association or stream-of-consciousness) and dream analysis, they aimed to reveal the subconscious through art.

Giorgio de Chiricos (1888–1978) painting Premonitory Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire depicts the poet Apollinaire as a black shadow; the bespectacled bust in the foreground refers to the mythical poet Homer, who was purportedly blind. Here, blindness becomes a symbol of looking inward, but also of poetic creativity.

Giorgio de Chirico, Premonitory Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire | Portrait [prémonitoire] de Guillaume Apollinaire, 1914

Thus, Friedrich and the Surrealists were pursuing the same goal: to make that which is felt—the invisible—visible.

3 »Romantic Ruins«

In Caspar David Friedrich’s art, ruins appear most often as evocative backdrops for his atmospheric landscapes. Architecturally idealized, crumbling church windows and monastery ruins are a reminder of the connection between human beings, nature and faith. Friedrich exaggerated real locations and modified them according to his own feelings, creating otherworldly places of longing.

Caspar David Friedrich, Ruins at Oybin, c. 1812

André Breton on „Romantic Ruins“

André Breton on „Romantic Ruins“, clip from the audio guide to the exhibition »Rendez-vous of Dreams. Surrealism and German Romanticism«, Hamburger Kunsthalle (transcript)

The founder of Surrealism, André Breton, saw ruins not only as the end of something, but also as an entrance to the unconscious, and to dreams. As he wrote himself …

… »The marvellous is not the same in every period of history: it partakes in some obscure way of a sort of general revelation only the fragments of which come down to us: they are the romantic ruins, the modern mannequin, or any other symbol capable of affecting the human sensibility for a period of time.«

Ruins also appear in the visual worlds of the Surrealists – here, however as sinister, out-of-control places. In Max Ernst’s work, the ruin becomes a field of rubble that is being reclaimed by nature.

Paul Nash reinterpreted Friedrich’s monumental painting Das Eismeer as a Totes Meer (Dead Sea): instead of ice floes, we see the wreckage of crashed planes piled up under a joyless wartime sky.

Caspar David Friedrich, The Sea of Ice, 1823/24

Paul Nash, Dead Sea, 1940–41

Max Ernst, Garden Airplane-Trap | Jardin gobe-avions, 1935/36

Max Ernst, The Entire City | La ville entière, 1935/36

For both the Romantics and the Surrealists, the forest was a place of transition, which increasingly became a mirror for the subconscious.

4 Waldeinsamkeit (Forest solitude)

In Caspar David Friedrich’s work, the forest is more than a collection of trees—it is a mythical place. Friedrich’s woods are dark, enchanted and often deserted. They appear to be all-powerful, and at times religiously or politically charged.

The Romantic author Ludwig Tieck (1773–1853) coined a unique word for the feeling of reverence, comfort and eeriness that the forest evoked in his generation: Waldeinsamkeit (forest solitude).

Max Ernst on his first encounter with the forest

Max Ernst on his first encounter with the forest, clip from the audio guide to the exhibition »Rendez-vous of Dreams. Surrealism and German Romanticism«, Hamburger Kunsthalle (transcript)

Max Ernst described his very first encounter with a forest as a mixture of …

… »delight and oppression. And what the Romantics called ’emotion in the face of nature’. The wonderful pleasure of breathing freely in the open space, yet at the same time the oppression of being surrounded and imprisoned by hostile trees. Outside and inside at the same time. Free and trapped.«

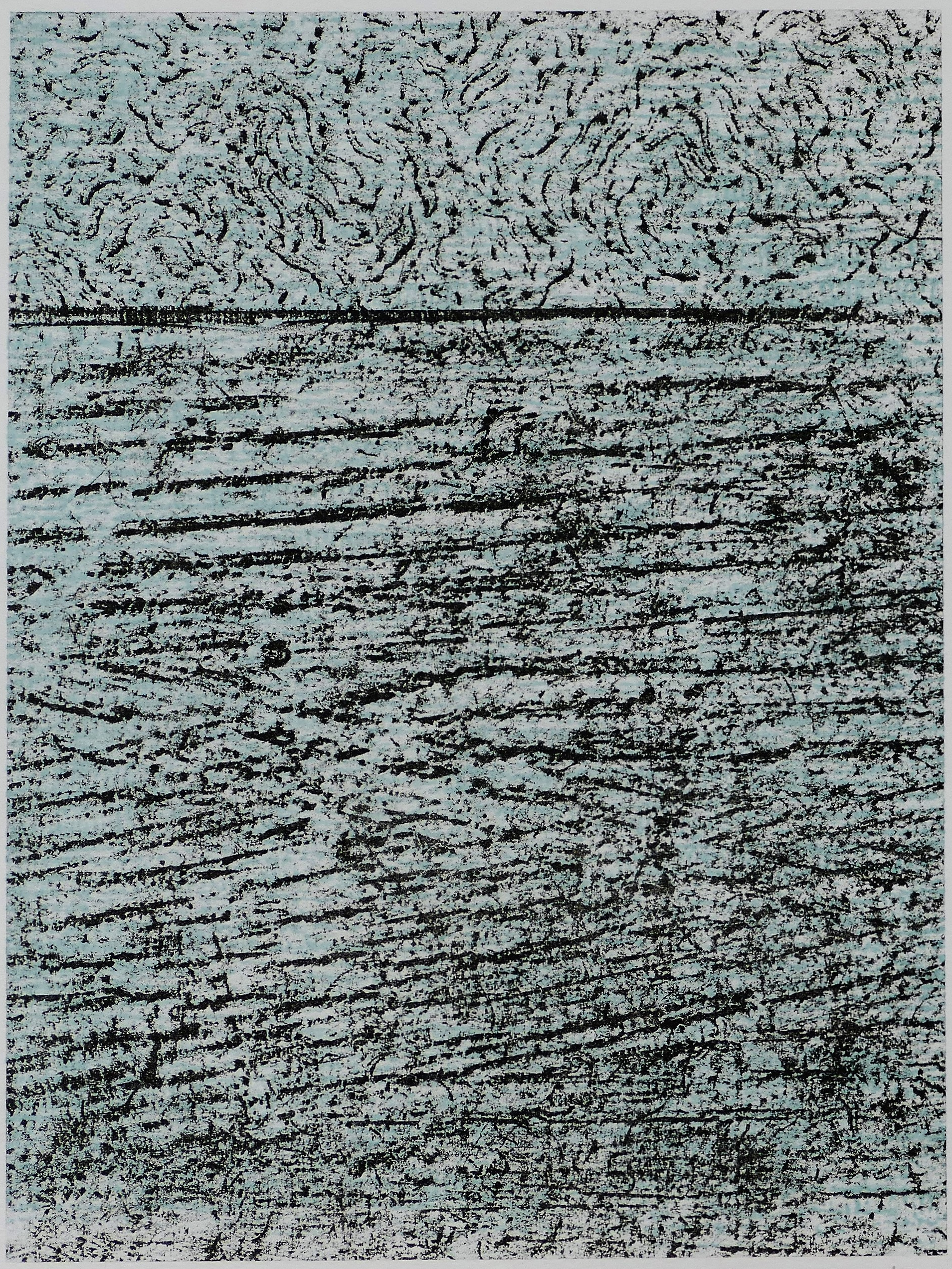

In Surrealism, the forest became more alive, otherworldly and even grotesque. Max Ernst rediscovered the forest as a motif in the 1920s. At that time he was beginning to experiment with the artistic techniques of frottage (making an impression of a textured surface by placing a piece of paper over it and rubbing it with chalk) and grattage (scraping away layers of oil paint applied over a textured surface).

For both the Romantics and the Surrealists, the forest was a place of transition, which increasingly became a mirror for the subconscious.

5 Hymns to the Night

Night plays a central role in both Romanticism and Surrealism. For Caspar David Friedrich, night was a time for pausing and for introspection. In his paintings he created nocturnal, almost sacred spaces—silent, melancholy and sublimely beautiful. A friend of Friedrich’s recalled that the artist once even commented self-mockingly on his penchant for moonlit landscapes:

He laughed at himself that he painted so many scenes of moonlight, and speculated that if people are transported to another world after they die, he would certainly end up on the moon.

Juxtaposition of infrared reflectography and Caspar David Friedrich’s painting Seashore in Moonlight, 1835/36

The photographic process of infrared reflectography gives us insight into Friedrich’s painting process. It allows us to see the layers of paint underneath Seashore in Moonlight, one of the last oil paintings Friedrich completed before his death in 1840.

Unlike the finished picture, the draft reveals even more ships sailing on the water. By omitting some of the ships, Friedrich intensified the image’s impression of a lonely moonlit night.

During the night, logic and order are suspended, setting the stage for absurd, erotic or nightmarish phenomena. In the nighttime images of the Surrealists, reality increasingly dissolves, opening up space for dreams, hallucinations and the unknown.

In drawing on the Romantic artists, the Surrealists by no means limited themselves to Friedrich. They were equally familiar with Carl Gustav Carus and Philipp Otto Runge, both of whom were influenced by Friedrich. Particularly in Runge’s complex pictorial worlds, we can see subjects and points of view that also appear in updated form in the works of the Surrealist artists. A fascination with the primal—personified as Mother Earth, for example—as well as plant symbolism, play a major role in both movements. In his theories, too, Runge followed directly on the early Romantic movements in Jena and Heidelberg: with their “progressive universal poetry,” they aspired to a world in which art and life permeate one another completely and have a reciprocal influence on each other. Surrealism sought a similar unity of life and art.

Runge and Friedrich were in contact prior to Runge’s early death in 1810; they had already met in Dresden around 1803. Friedrich’s correspondence with scholars in the fields of theology, natural philosophy and the natural sciences shows that he also occupied himself with scientific questions.

Philipp Otto Runge, Dog Barking at the Moon, 1803

Joan Miró, Dog Barking at the Moon | Chien aboyant à la lune, 1926

Whereas Friedrich’s night is an invitation to spiritual exploration, in Surrealism, the night is a somnambulistic playground for the psyche.

In both cases, however, the night represents that which exists beyond the visible world—be it the divine or one’s own subconscious.

6 Max Ernst and Caspar David Friedrich's Monk by the Sea

The Surrealist painter Max Ernst explored German Romanticism intensively. He was particularly influenced by Heinrich von Kleist (1777–1811) and Caspar David Friedrich:

The fact is that Friedrich’s paintings and his perspectives have been more or less consciously in my mind almost since I started painting.

Kleist was a contemporary of Friedrich’s; he saw Friedrich’s painting Monk by the Sea at its first public exhibition in Berlin in 1810—and was immediately captivated. Deeply moved, Kleist summed up his visual experience in 1810:

»Nothing can be sadder or more desolate than this place in the world: the only spark of life in the vast realm of death, the lonely central point in the lonely circle. The image lies there, with its two or three mysterious objects, like the Apocalypse, as if it were thinking Edward Young’s ‘Night Thoughts’—and since, in its uniformity and boundlessness, it has nothing but the frame for a foreground, one feels, as a viewer, as if one’s eyelids had been cut off.«

Ähnlich „schneidend“ sind die Bilder, die Salvador Dalí und Louis Buñuel für den surrealistischen Film Ein andalusischer Hund 1929 fanden.

Auch hier markiert der (wahrhaftige) Schnitt durchs Auge die radikale Abkehr von herkömmlichen Sehgewohnheiten hinein in innere Welten.

Caspar David Friedrich, Monk by the Sea, 1808–10

Max Ernst, Seelandschaft mit Kapuziner (Seascape with Capuchin), To: Kleist, Brentano, Arnim: Caspar David Friedrich, Paysage marin avec un Capucin | Seelandschaft mit Kapuziner, translated by Max Ernst, Zürich 1972.

Max Ernst only became aware of Kleist’s commentary on Friedrich’s exhibition in the 1960s. He immediately translated the text into French and supplemented it with an illustration of his own.

With his lithograph Seelandschaft mit Kapuziner, Ernst produced his own take on Friedrich’s painting, whose earlier title was “Seelandschaft mit Kapuzinermönch” (Seascape with a Capuchin Monk). Frottage-like printed-through surfaces communicate the relationships from above and below, back and front. The churning, animated sky is nearly pushed out by abstract, wavelike strokes.

Are we now completely immersed in the brooding interior of the solitary figure on the beach?

In Caspar David Friedrich, Max Ernst recognized a spiritual kinsman and a predecessor of Surrealism—in his idea of the inwardly experienced landscape, the night and the forest as spaces of contemplation and glimpses of the superhuman, his radical reductions. Ernst’s own works reveal parallels to Friedrich’s world of symbols, but they exaggerate it into dreamlike (or nightmarish) one.

The dialogue between Caspar David Friedrich’s art and Surrealism shows us:

The movement that began as Romanticism around 1900 had a surreal rebirth over 100 years later—dreamlike, menacing, and poetic.